May 1 is returning to its historic roots as a day of worker protest, this reprise targeting Trump.

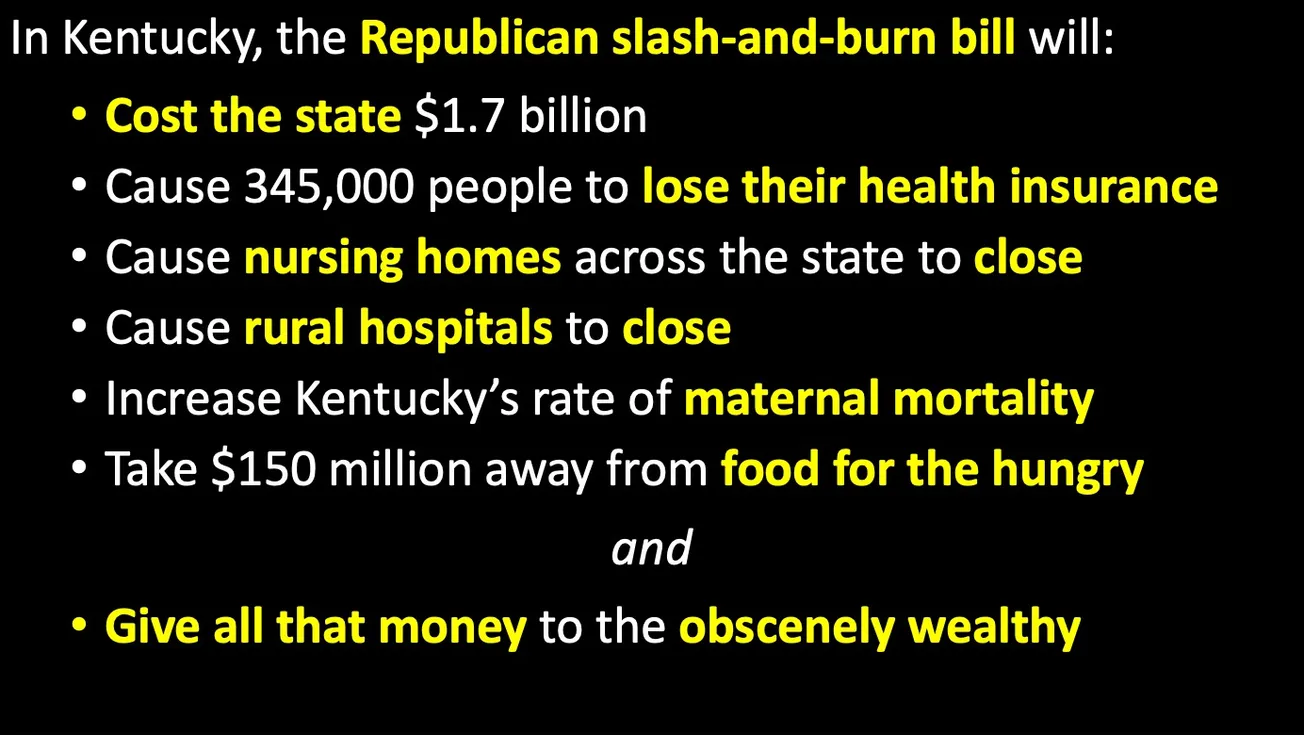

“As labor unions and rights advocacy groups announced a mass mobilization planned for May 1, or May Day, one leader said the protests aim to ‘send a loud and clear message’ to U.S. President Donald Trump, his adviser Elon Musk, ‘and the rest of the billionaire oligarchs trying to destroy our democracy,’” wrote Julia Conley in Common Dreams.

Rallies and marches against Trump’s “billionaire agenda” are scheduled for all 50 states and more than 600 cities and towns, she added.

Kentucky May 1 protest sites include Louisville, Lexington, Hopkinsville, Benton, Hazard, Franklin (twice), Covington, and Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky. Protests are set for May 3 in Paducah and Owensboro.

Kentucky State AFL-CIO President Dustin Reinstedler will speak at the Louisville rally. Liles Taylor, state AFL-CIO political coordinator, is slated to speak in Lexington.

“I am thrilled that people are waking up,” Reinstedler said. “People are finally starting to see that the attack on the working class is real – that there are two classes, the working class and the ruling class.”

He suspects many people in the Derby City crowd will be “newly engaged and maybe not from union backgrounds. But I suspect everybody there will be working class. I don’t think there will be any billionaires.”

He also said his speech will provide him “a good opportunity to educate people in the crowd about what May Day is.”

Officially International Workers’ Day, May Day stems from worker demands for the eight-hour workday, which most employers opposed.

In late 19th-century America, 12- and even 16-hour days were common. A handful of industrialists made millions of dollars by impoverishing millions of workers.

The American Federation of Labor, an organization of craft unions, urged all workers to strike on May 1, 1886, in cities and towns where employers rejected the eight-hour day, explained Howard Zinn in A People’s History of the United States.

As a result, “350,000 workers in 11,562 establishments all over the country went on strike,” he wrote.

When workers struck for the eight-hour day at the sprawling McCormick Harvester Works in Chicago, management locked them out and hired strikebreakers. Strikers and sympathizers gathered outside the plant and clashed with scabs. On May 3, police showed up “and fired into a crowd of strikers running from the scene,” Zinn wrote, adding that four who fled were killed and several wounded.

Angered by police gunning down unarmed and unresisting workers, local labor leaders, including anarchists, called for a May 4 rally at Haymarket Square in support of the strikers and the eight-hour day. As the rally was winding down, police showed up. Suddenly, a bomb exploded among them, “wounding sixty-six officers, of whom seven later died,” wrote Zinn. Enraged, the officers who were unhurt opened fire on the crowd, killing many and wounding 200.

The bomb thrower was never identified. Without a shred of hard evidence linking them to the bomb, eight anarchists were convicted by an openly anti-union jury and sentenced to death by an avowedly anti-union judge. Four defendants were hanged, one committed suicide behind bars, and three languished in prison until they were pardoned in 1893 by Gov. John Peter Altgeld, who denounced the trial as a tragic miscarriage of justice.

In 1889, the International Socialist Conference proclaimed May Day a labor holiday in honor of the Haymarket martyrs. Today, International Workers’ Day is celebrated by workers almost everywhere – except in the United States and Canada. Observed on the first Monday in September in both countries, the holiday is “Labor Day” stateside and “Labour Day” north of the border.

Explained National Public Radio’s Emma Bowman: “U.S. resistance to celebrate International Labor Day — also called International Workers’ Day — in May stems from a resistance to emboldening worldwide working-class unity, historians say.”

She quoted American historian Peter Linebaugh, author of The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day: “The ruling class did not want to have a very active labor force connected internationally. The principle of national patriotism was used against the principle of working-class unity or trade union unity.”

In the late 19th-century, American industrialists and their political allies also feared that European socialism and labor militancy would spread to the U.S., where — absent unions — workers, including women and children, toiled long hours at low pay in dangerous and even deadly conditions. Wealthy factory, mine, and mill owners bitterly — and often violently — battled unions.

President Grover Cleveland, a conservative, pro-business Democrat, feared that a May Day holiday might encourage international solidarity among workers and help popularize socialism in America. He sided with more conservative American unions that favored a September holiday.

In 1894, after Labor Day had become an early September holiday in 23 states, Congress approved legislation fixing the first Monday in September as a national holiday. Cleveland signed the measure on June 28.

Meanwhile, the ongoing Pullman strike, led by Eugene V. Debs and the American Railway Union, was stalling rail traffic over much of the country. (Debs ran for president as a Socialist five times, the last time from behind bars for opposing the draft and World War I, which he saw as a needless conflict between two imperialist European power blocs fought by workers who had no stake in the outcome.)

Siding with management, on July 3 Cleveland dispatched the first contingent of federal troops to Chicago, the center of the strike, which afterwards collapsed. Debs was jailed for refusing to lift the strike.

(Using military force to end strikes was bipartisan in the post-Civil War period. Conservative, pro-business Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes dispatched federal troops to break the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Several governors, both Democrats and Republicans, called out state militias to defeat strikes.)

In Canada, Labor Day started on April 15, 1872, in Toronto where local unions “organized the country’s first significant ‘workers demonstration.’” American Labor Day observances, starting in the 1880s, were “inspired by the beginnings made in Canada,” according to the Canadian National Union of Public and General Employees.

U.S. conservatives redoubled their efforts to discredit International Labor Day during the Cold War. Though workers in other democracies celebrated (and still celebrate) the holiday, the American right, ever anti-union and fearful of international worker solidarity, smeared May 1 as a Communist observance.

Despite the fall of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in eastern Europe three decades ago, some Americans still associate May 1 with communism, according to Bowman.

“Labor Day has put May Day in the shadows,” Reinstedler said, wryly noting that presidents and congresses “sometimes can be bought and paid for.” He wants “people to know we are not on that team – that we are 100 percent pro labor and 100 percent pro-worker.”

Reinstedler pointed out that more than union members gathered outside the McCormick plant and rallied at Haymarket. “It was a true community effort and an example of what we can strive for today.”

--30--