I’m thinking about my old Sunday School teacher.

On June 6, 1944, First Lt. Frank Kolb of the Army’s First Infantry Division sprang from a landing craft on Omaha Beach in Normandy, France. The Paducah native was one of about 160,000 Allied troops, mostly British, American, Canadian, and Free French, who spearheaded the largest air and sea invasion in the history of warfare.

The attackers — parachutists and ground forces — faced 50,000 German troops dug in on clifftops that were well-protected by concrete bunkers and trenches bristling with cannons and machine guns. Barbed wire, anti-tank obstacles, and mines were on the beaches and in the surf. The enemy called its coastal defenses the “Atlantic Wall.”

The attack — code named Operation Overlord — went down in history as “D-Day,” and it opened the long-awaited second front in Europe in World War II.

A total of 4,414 Allied troops were killed 80 years ago tomorrow. The death toll included 2,501 Americans.

More than 5,000 Allied soldiers were wounded.

Miraculously, Kolb survived unscathed, though more than 700 men were killed and 1,700 wounded on the six-mile strip of sand and pebbles dubbed “Bloody Omaha” because casualties were highest here among the five code-named invasion beaches: Utah and Omaha (American), Gold (British), Juno (Canadian) and Sword (British).

Kolb hurried ashore under heavy fire about 20 minutes after the first wave of the storied “Big Red One” hit the beach. The first wave suffered the heaviest losses.

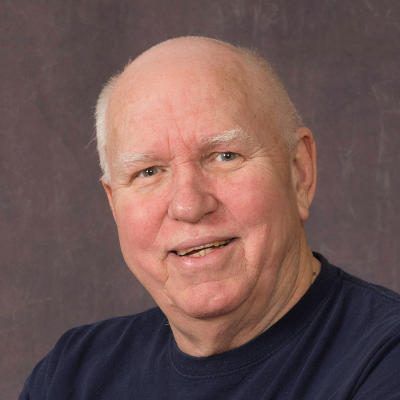

Kolb, who died in 2000 at age 77, moved to Mayfield after the war, married Grace Walter, and joined the First Presbyterian Church. The couple reared a son and three daughters.

Between late 1942 to the war’s end in May, 1945, Kolb’s bravery earned him four Silver Stars, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart (he was wounded later in the war). He fought in seven campaigns with the First Infantry Division. He might have been the division’s youngest-ever company commander.

Kolb watched the 1998 movie Saving Private Ryan with the late Dan Garrott, also a member of Mayfield First Presbyterian. Former Staff Sgt. Garrott arrived in Normandy after D-Day but won a Silver Star and a French Croix de Guerre for valor in fighting across France and Germany.

Kolb described the film’s harrowing opening scene when the Americans are pinned down on the beach simply as “very realistic.” He was a man of few words.

When I grew up in the 1911-vintage red brick church, a casualty of the 2021 tornado that devastated much of Mayfield, several of the middle-aged men in the congregation were combat veterans of World War II. They included my ex-sailor father, who served aboard a landing craft and a minesweeper in the Pacific. They’re all gone.

My interest in history was already keen when I was a 13-year-old eighth grader at Mayfield’s W.J. Webb Junior High School.

I was a regular patron of the Graves County Library – then in the old stone Gardner home on College Street. One day, I checked out Irving Werstein’s book, The Battle of Aachen.

The author wrote that 21-year-old Lt. Frank Kolb and his men “were the first American soldiers to set foot on German ground.” I was shocked. On Sept. 13, 1944, near Aachen, the guy who taught my junior high Sunday school class and his troops beat everybody else through Hitler’s vaunted “Westwall,” a wide belt of barbed wire, mine fields, anti-tank obstacles, and concrete pillboxes that Allied troops nicknamed the “Siegfried Line.”

Naturally, the next Sunday, I asked him about what the book said. He politely declined my inquiry and suggested we proceed with the lesson.

Kolb didn’t talk to me about his role in World War II until 1999. I was teaching history at West Kentucky Community College in Paducah and freelancing for the Associated Press in Louisville.

I don’t know why he finally relented. I knew him as a quiet, soft-spoken man who shunned the limelight. But he was dying of cancer. So maybe he wanted the public to know his story before he died.

The interview at his home lasted for several hours. He didn’t spare me the horrifying details. “Don’t make me sound like a hero,” he warned me as I was leaving. I replied that his story would speak for itself.

The AP ran the story, which appeared in several daily newspapers statewide, including the Paducah Sun, where I was a feature writer before forsaking the newsroom for a classroom. His son, the late Dr. John Kolb, a Paducah physician, phoned to tell me his father had never talked about that part of the war to him. I heard similar comments from the grown children of other World War II vets I interviewed for AP stories and for some of my books. I have always suspected that, though they wanted to shield their children from the horrors of war, they also wanted their stories told before it was too late.

I have walked the length of Omaha Beach three times, twice with Melinda and once with Berry IV, when he was nine.

There, where German and American soldiers tried mightily to kill each other on June 6, 1944, families now happily stroll on sunny June days. Boys and girls splash in the surf or build castles in the sand. Sun bathers relax on beach towels and in beach chairs. Wind surfers skim across the shallows; sailboats and small motor boats glide past offshore.

Nearby, there was — maybe still is — a snack bar that sold hot-dogs américains.

A few steps away is the concrete hulk of a German artillery bunker that was turned into the Army National Guard Memorial.

I ended my last book, Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy by quoting from Tom Brokaw’s book, The Greatest Generation: “This book, I hope, will, in some small way pay tribute to those men and women who have given us the lives we have today.”

I’ll add a Presbyterian “amen” to that.

The famous TV journalist added, “I’m in awe of them, and I feel privileged to have been a witness to their lives and their sacrifices.” Likewise, I feel privileged to have interviewed and written about maybe two dozen of them.

The fourth page in my Pearl Harbor book is the dedication page, which reads “To my father, the late Motor Machinist’s Mate First Class, Berry F. Craig Jr., US Navy, and my father-in-law, the late Master Sergeant Robert Hocker Jr., US Army, both of whom enlisted after Pearl Harbor and came home with battle stars on their Asiatic and Pacific campaign ribbons.”

Few D-Day veterans, indeed few of the Greatest Generation, are still with us. All those I interviewed are gone. None of them claimed to be war heroes. But heroes they were. They didn’t call themselves The Greatest Generation either. But they were.

--30--