You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: ‘Now, you are free to go where you want, and do as you desire, and choose the leaders you please.’ You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.

Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates.

This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result. – President Lyndon B. Johnson, Howard University Commencement address, 1965

“People of color have a constant frustration of not being represented, or being misrepresented, and these images go around the world,” said filmmaker Spike Lee.

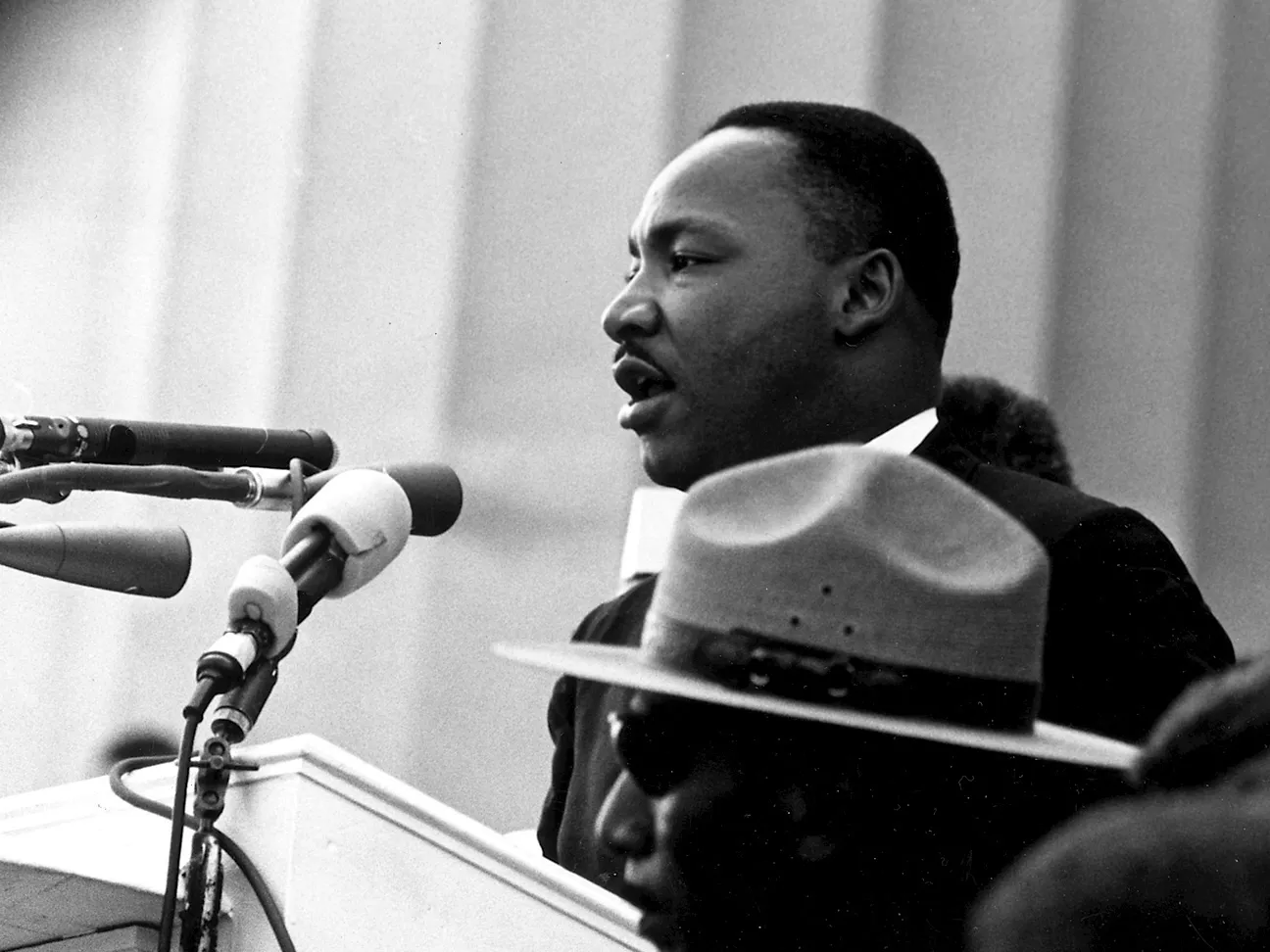

Such has been the fate of the “I have a dream” line from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech.

To justify their opposition to federal civil rights laws — notably affirmative action and, of late, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs — conservatives quote out of context this one line:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Murray State University historian Brian Clardy is “sick to death with conservatives and reactionaries distorting the words, life, ministry, and contributions of Martin Luther King.”

History, of course, is replete with examples of the unscrupulous twisting the words of the deceased to suit their own ends.

Bernice King responds to the president and the pastor twisting her father’s words

In his recent inaugural address, President Donald Trump cynically invoked King’s words. So did the Rev. Lorenzo Sewell in his inaugural prayer. (Trump’s inauguration happened to fall on this year’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day federal holiday, which is observed on the third Monday in January, King’s birth month in 1929.)

Bernice King, King’s youngest daughter, denounced both of them for misrepresenting the meaning of her father’s speech, wrote Kimberly Richards in HuffPost.

King, according to Richards, posted a video clip from Sewell’s prayer on X and took the pastor to task: “I don’t deny the power of my father’s most well-known speech. However, its power and popularity (with focus on its conclusion) have been misused to weaken its clear messaging about ending racism, stopping police brutality, ensuring voting rights, and eradicating economic injustice.”

King wondered why Sewell chose not to “pray these parts of the Dream during President Trump’s Inauguration.”

She also wrote: “The inconvenient truth (that disallows embracing the pipe dream that racism no longer exists in this country) is that Project 2025 and some of the plans that his voters encouraged POTUS to roll out on day one are reflective of an ‘America’ that denies the comprehensive King.”

Trump ran the three most racist presidential campaigns since George Wallace in 1968. Even so, Richards noted that he vowed, “We will strive together to make [King’s] dream a reality” and later promised, “We will forge a society that is colorblind and merit-based.”

Richards wrote that “Trump’s ‘merit-based’ remark was a callout to the ongoing crusade led by conservatives — and now helped by his new executive actions — against diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.”

King’s daughter “has long rejected any suggestions that her father’s speeches or work demonstrate that he would support the idea of racial colorblindness, or that he’d oppose affirmative action or DEI practices today,” Richards wrote.

King, according to Richards, posted on X in 2023 that “People using ‘not judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character’ to deter discussion of, teaching about, and protest against racism are not students of the comprehensive #MLK. My father’s dream and work included eradicating racism, not ignoring it.”

‘A call for justice’

Clardy said the “I have a dream” part of the speech comes at the end. “The early part of the speech is a call for justice, fairness, equality, and inclusion. You add to that everything else that King had done in his life also spoke to the issues of fairness and equality even when it came to the prosecution of [the Vietnam]…war and also economic justice.”

A white supremacist assassin ended King’s life in 1968 with a rifle shot in Memphis, where he had gone to stand in solidarity with striking sanitation workers who were members of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees.

“That radical part of King post-1963 is never mentioned by the right,” Clardy said. “Trump has given license and voice to a lot of these sentiments that many of these closeted bigots have held all this time. Now they feel free to say whatever they want to. Now with him back in the White House, they are emboldened, and he and people like him are going to say much worse.”

Clardy is hardly alone in rebuking conservatives who distort the true meaning of King’s words. “Many historians, professors, and experts on race and race relations in the U.S. have similarly called out attempts to connect Martin Luther King Jr.’s fight for justice and equality to the idea of colorblindness,” Richards wrote.

She cited scholars, including Lerone A. Martin, Stanford University professor of Religious Studies and of African and African American Studies; and University of Southern California professor of Education, Business and Public Policy Shaun Harper.

Martin said on CNN last January “that the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech has been repeatedly misinterpreted to mean a call for ‘the dismantling of various mechanisms that were intended to bring about a more equitable society.’”

Richards added, “Martin, who is also the director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, said that the entirety of Martin Luther King Jr.’s work — including his 1967 book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community, in which he assesses the next phase of the movement for social justice — proves that he did not promote colorblindness.”

Richards also wrote that Harper “said that anyone who thinks the late activist would be in favor of dismantling DEI initiatives that ‘aim to right America’s historical and present-day wrongs against people of color, women, and poor Americans’ don’t understand who Martin Luther King Jr. was and ‘what he actually fought and died for.’”

Harper, according to Richards, “told HuffPost that he believes the late King would be ‘repulsed’ by people taking his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech out of context.”

Said Harper: “Surely, he didn’t mean for those words to be misused to deny Black people race-salient, well-deserved, long-overdue remedies to centuries of racial violence, discrimination, and harm against us in this country.”

In a Rolling Stone article, Andrew Perez and Tomás Mier also quoted Martin, who, in a recent interview on CNN on Sunday, “criticized folks who “often misinterpret MLK’s words as a ‘call for color-blindness.’”

Said Martin: “Colorblindness asks us to explain systemic racial inequality by using ‘raceless’ explanations,” Martin said. “It asks us to explain or solve a phenomenon but bars us from addressing the root cause of the phenomenon.”

Perez and Mier also quoted from a 2021 Daily Beast op-ed written by Rolling Stone contributor Ernest Owens: “For years, conservatives have romanticized a revisionist history of King as their model Black citizen – even though he was an outspoken activist who spoke against American wars, was labeled a communist, and supported more social services for the people. King has been reduced to a few quotes about nonviolence that these cynical Republicans use to chastise living Black leaders and organizers whom they despise.”

Clardy said the current conservative onslaught against DEI and “wokeism” is rooted in the hoary right-wing “reverse discrimination” trope. “The depiction of DEI initiatives as ‘reverse discrimination’ are as old and outdated as the illogic upon which it is based.

“The trope assumes that central government programs are designed to elevate an ignorant and irresponsible people to higher stations in society at the expense of qualified whites. This is clearly not the case. Indeed these programs allow for people across the racial and gender-based spectrum to have the right to participate in the mainstream of American life, although they had been unable to do so because of structural barriers that were ensconced in the nation’s founding.”

He pointed out that from slavery times to the middle of the last century, Blacks “were frozen completely out of the bastions of higher education, thus rendering them unable to compete in the life of the nation. Granted, there were some exceptions due to the fact that the historically Black colleges and universities enabled a few to aspire to white collar jobs. But it was the policy of many state universities to exclude people of color.”

The King and Trump visions – a comparison

Because the King holiday and inauguration day coincided this year, the Las Vegas Sun published an editorial comparing the King and Trump visions:

“Most Americans know King through the iconic lines of his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech – a powerful moment of soaring rhetoric captured on camera at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Yet, for all its power, this speech is too often taken out of context and manipulated for political ends, a disservice to King’s vision and the movement he led.

“The line ‘I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character’ is too often used to justify a ‘colorblind’ society that ‘doesn’t see race’ and thus avoids or ignores conversations about racial discrimination and disparities in our society. This interpretation not only distorts King’s message, but also weaponizes it to perpetuate the very inequalities he fought against.

“While King may have dreamed of a day in which race was treated as just another unremarkable attribute of an increasingly diverse society, he understood that achieving that dream required not only acknowledging that race exists, but confronting the painful role that race has played and continues to play in dividing communities and impeding the promise of equality, opportunity and prosperity for all.”

The editorial also said that “... Trump’s rhetoric and policies have often stoked division, prioritizing nationalism over mutuality and favoring economic policies that widen the gap between the wealthy and the working class. Where King envisioned a society that lifts everyone, Trump’s vision has often been one of exclusion, emphasizing competition over cooperation and personal gain over collective well-being. A number of those approaches are consistent with capitalism conceptually; however, in Trump’s application there is always a heavy hand on the scale tilting the advantage to one party over another rather than allowing people to compete purely on merit.

“The contrast between these visions is stark. King’s dream challenges us to build bridges and to never forget the importance of the least powerful among us; Trump’s rhetoric has too often sought to build walls and celebrate the naked exploitation of power. King’s vision calls for solidarity across race and class; Trump’s policies have frequently deepened divides. As we honor King today, we must ask ourselves: Which vision will guide America’s future?”

Which indeed?

“Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance,” King wrote in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? “It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.”

The book is as relevant as ever — especially with “conservatives and reactionaries distorting the words, life, ministry and contributions” of King so willingly and so shamefully.

--30--