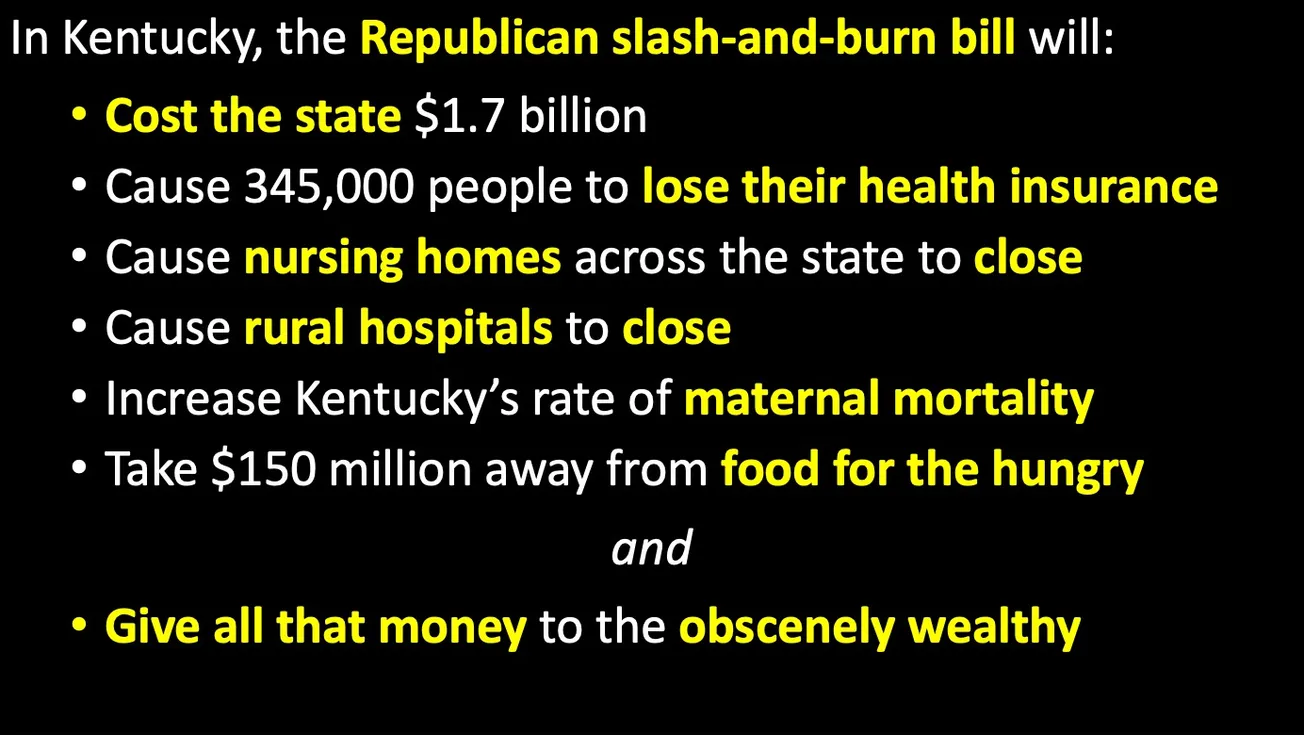

In Washington, Rep. Andy Biggs (R-AZ) has reintroduced legislation to abolish the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. He calls it the “NOSHA bill.”

Biggs, who despises unions, insists that state governments and private employers would do a better job of taking care of job safety and health than Uncle Sam.

And in Frankfort, Republican-backed House Bill 398, legislation which would wreck the Kentucky Occupational Safety and Health program, seems poised for final passage in the GOP supermajority General Assembly.

“This bill is not just an attack on workplace safety – it’s an attack on every working Kentuckian,” wrote Kentucky State AFL-CIO President Dustin Reinstedler in a Louisville Courier-Journal op-ed.

Other MAGA GOP-majority legislatures and governors are pushing similar measures.

So what happens if we leave safety up to the employers? When safety was left up to the bosses, it meant factories, mines and mills were slaughterhouses where workers risked — and often lost — lives and limbs.

I don’t know if Biggs, Donald Trump, Elon Musk or national and state MAGA politicians have ever heard of a brutal rightwing economic philosophy called Social Darwinism. But it’s back in spirit, and with a vengeance.

Social Darwinism was wildly popular with late 19th- and early 20th-century Robber Barons – the forebears of billionaires like Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg, who showed up to genuflect to Trump at his second inauguration.

Social Darwinists preached that the economy worked like nature: the strong survived, and the weak perished. Thus, they said anything that interfered with the “natural operation” of the “free market” must be opposed. They especially meant unions and worker safety and health laws.

One Social Darwinist said job safety laws were a waste because they only protected “those of the lowest development.”

More than a century ago this month, the Social Darwinian perspective resulted in one of the deadliest industrial tragedies in U.S. history. “Accident” is not the right word because the bloodshed could have been prevented.

The horror that made newspaper headlines worldwide began on the afternoon of March 25, 1911, at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York. Triangle was one of several sweatshops in the city. Most Triangle employees were women. Most were immigrants, too.

They and other sweatshop workers had gone on strike in 1909, joining the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. Sweatshop owners stubbornly resisted the ILGWU and its demands for humane working conditions. “The strike went on through the winter, against police, against scabs, against arrests and prison,” Howard Zinn wrote in A People’s History of the United States.

Fire was the immediate and ever-present terror of sweatshop workers. About 4:40 p.m. a blaze broke out in a rag bin at the high-rise factory in the Asch Building. The flames raced through the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors. Fire department ladders reached no higher than the seventh floor.

“But half of New York’s 500,000 [sweatshop] workers spent all day, perhaps twelve hours, above the seventh floor,” Zinn wrote.

Local laws required factory doors to open outward. That would make escape easier in case of fire. Triangle’s owners ignored the laws. Factory doors opened inward, according to Zinn.

Local laws also mandated that factory doors could not be locked during working hours. This was also to help people survive a fire. Triangle owners ignored those laws, too. They locked the doors to keep track of employees, Zinn wrote.

“And so,” the historian added, “the young women were burned to death at their work-tables, or jammed against the locked exit door, or leaped to their deaths down the elevator shafts.”

He quoted The New York World: “… Screaming men and women and boys and girls crowded out on the many window ledges and threw themselves into the streets far below. They jumped with their clothing ablaze. The hair of some of the girls streamed up aflame as they leaped.

“Thud after thud sounded on the pavements. It is a ghastly fact that both the Greene Street and Washington Place sides of the building there grew mounds of the dead and dying. … From opposite windows spectators saw again and again pitiable companionships formed in the instant of death – girls who placed their arms around each other as they leaped.”

The fire killed 146 workers – including some women in their teens.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was not an isolated incident – far from it. In the 1900s, thousands more workers were killed or maimed in accidents — most of them preventable — or were made seriously ill at work through exposure to hazardous substances employers knew or suspected were harmful.

Now called the Brown Building, the structure belongs to New York University. A bronze plaque on an outside wall commemorates the deadly tragedy.

“NYU came to own a piece of that history when Frederick Brown donated the building to the university in 1929,” explains the NYU website. “Now, each March, the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition organizes a ceremony to commemorate the tragedy at the corner of Green and Washington Place, in the heart of the Washington Square campus. In 2011, the Grey Art Gallery mounted a special exhibition for the 100th anniversary of the fire.”

On April 2, 1911, labor activist and Jewish immigrant Rose Schneiderman delivered a powerful speech at the Metropolitan Opera House protesting the fire and shaming the audience. Her words still ring true as latter-day, reactionary politicians aim to destroy meaningful government worker and safety laws at the state and federal levels.

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers, and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable, the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us — warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.

--30--